Iceland was our gateway to Greenland’s East coast. We all landed in Reykjavik on July 13th in the evening, and drove through the night to the little harbor of Húsavík on the north coast. The next morning, we got onboard the Donna Wood, a 100-year old Danish lighthouse ship used today by the whale watching company North Sailing for tours in Greenland. It took three days to sail across the Arctic ocean to the 400 people strong settlement of Ittoqqortoormiit, one of the most isolated village on earth.

There, we switched our oak boat for a small open motor boat owned by Ingkasi, an inuit hunter with whom we’ve been in touch. After purchasing some final supplies like fuel and rifles – in case of troubles with bears or muskoxen – we transferred our team of 14 people across the Scoresby Sund, the largest fjord system in the world, to the small Skillebugt fjord, a notch cut into the round shape of the Renland peninsula. We had with us around 1200kg of equipment: food (including a large part of dehydrated meals), fuel, scientific equipment, climbing and mountaineering gear, photo and video equipment, power generators (both solar- and fuel-based) and batteries, along with our personal things.

We used a small boat owned by a local hunter to move across the vast expanses of water dotted with icebergs of the Scoresby Sund

We used a small boat owned by a local hunter to move across the vast expanses of water dotted with icebergs of the Scoresby SundWe would stay 3 full weeks on the Renland peninsula, spread over 4 basecamps. Its glaciers and moraines are the place where three of our scientists from the CNRS (France’s National Scientific Research Center), Eric Larose, Agnès Helmstetter and Ludovic Gielly, had intended to carry out their research projects. Samples were first taken in moraines near the fjord, in recently deglaciated area. Environmental DNA tests will reveal how these environments are colonized following the glaciers’ retreat – something similar to what took place in the Alps thousands of years ago.

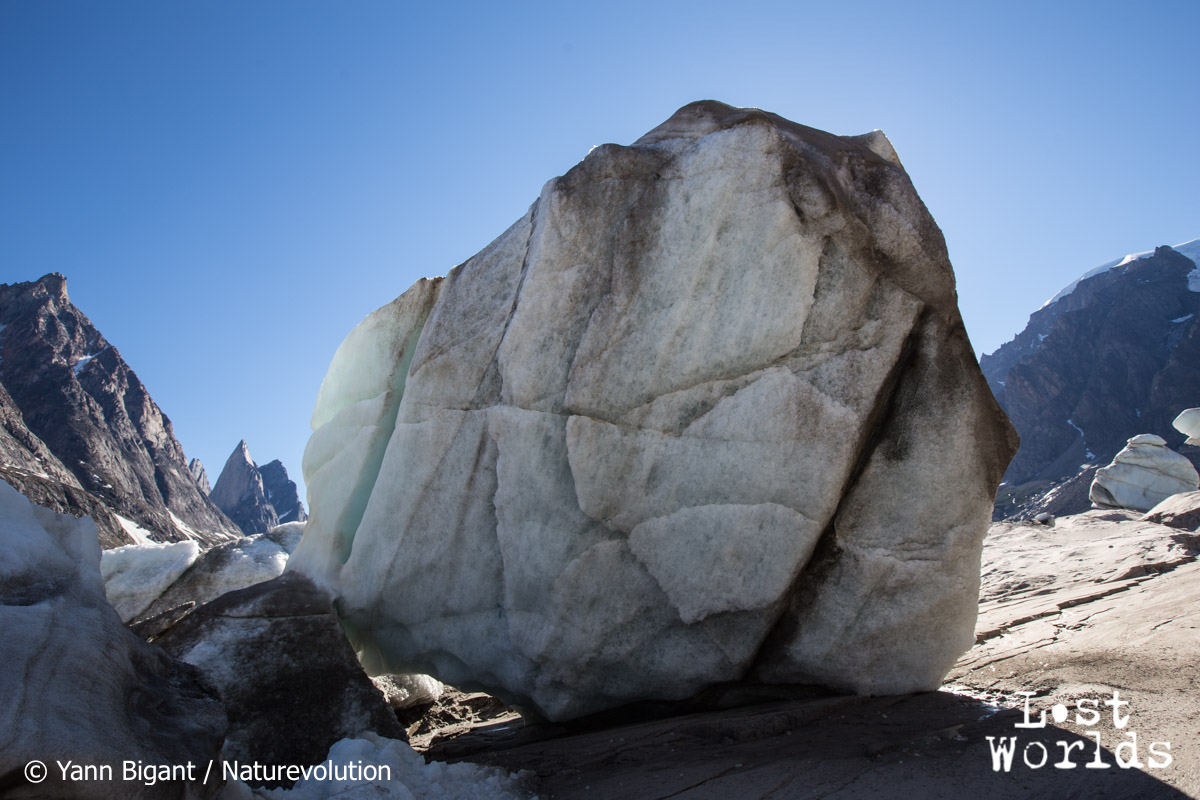

From Camp 0 located near the Skillebugt fjord, we searched for a way amidst tricky moraines to get onto the Apusinikajik glacier. Once on its surface, just 2 hours’ walk took us across to its second front, and we established Camp 1 among sand dunes, right next to a little lake full of icebergs bordering the glacier’s front. From the satellite images that we received several weeks before our departure, we knew that this lake used to be much bigger. In the meantime, it had drained and icebergs dotted its surroundings, stranded on the sand, creating a surreal, otherworldly landscape. We equipped both this first glacier and the sandy area near Camp 1 with seismic sensors to record the glacier’s activity and understand its mechanics. A small moulin on the glacier was explored : we could go as far down as 47meters ; it was also instrumented with sensors at the bottom and with two lines of geophones on the surface.

An unexpected finding was that the sandy area near Camp 1 lays on top of ice. The ice was sometimes just a meter under the sand, and up to 30m below it in other places. That ice was still : stuck between the Apusinikajik glacier and the large Edward Bailey glacier, it cannot move anymore, and the sand and moraine on top of it prevents it from melting. It could be “fossil ice” — remains from an older glacier that disappeared from the surface.

Again, we looked for a way towards the Edward Bailey glacier, an oversized glacier that drains most of the Renland icecap. Through a labyrinth of sand dunes, rock-covered ice ridges and moraines, we found an access route to the glacier’s surface. These glaciers are so large and active that their moraines are chaotic terrains to negotiate. We set up Camp 2 on the other side of the valley, in a flat stretch dotted with round rocks and home to Arctic hares.

Having so many people and scientific equipment means that each new camp induces several days of portage. Food, scientific equipment and mountaineering gear need to be carried between the various camps. For environmental much more than financial reasons, we chose to rule out using a helicopter and to carry instead everything on our backs. This had an impact on the research projects, but most important it helped us to understand the geographic and geological environment : how the glaciers and moraines work out, and most important, how immense everything is around here. The satisfaction then to reach a new camp by our own means is unique.

Camp 2 was just minutes away from the massive exit river of the Edward Bailey glacier. Though the underground river was coming out of the ground through a resurgence, two old tunnels located just above were adequate for exploration. We could go up 150 meters in one tunnel: 2 to 4 meters in diameter in place, its wall were smooth, shiny ice, and little water actually drained this way. The other cave was much smaller, but home to ice crystals of a surprising pyramidal square shape. The seismic activity of the glacier was recorded with sensors left in place for over a week.

We then made an advanced camp further up on the Edward Bailey glacier. With just very light equipment (yet still heavy bags…), we reached Camp 3 after a day’s walk on a “highway of ice”. This is the location of the glacier’s difluence, where it comes down from the icecap into a wide valley and separates into two branches going in opposite directions. We stayed there a few days exploring a stunning moulin, glacier rills perfect for pack rafts, and the neighboring lake of Catalina Dal. This lake is yet again another mystery, as how it actually drains into the sea is not fully understood yet : as the lake is the valley’s lowest point, somehow its water is either pushed higher by ice pressure, or it drains through tunnels under the glacier. Interestingly, while the glacier’s surface comes level with the lake, underwater, the interface between the lake and the glacier is actually an ice cliff of at least 60meters high — perhaps much more.

Packrafting across the Catalina Dal lake to explore a high point and get an overview of the landscape

Packrafting across the Catalina Dal lake to explore a high point and get an overview of the landscapeIt was then time to head back to the fjord. We had pushed our food supplies to the limit, and to save time we walked long hours to carry as much equipment down as fast as possible. That took us back to Camp 0 (and our food storage) in 2 exhausting days of 12-14 hours each. After a day’s rest, only two more days were necessary to carry the rest of the equipment down where it could be picked up by the boat.

While we were on Renland, our two biologists – the wildlife ecologists Tanguy Daufresne and Nicolas Gaidet – remained on the vast tundra spread of Jameson Land. One of their research project focused on the Arctic wolf and intended to determine whether it has recolonized Greenland as far south as the Scoresby Sund, especially in the area of Colorado Dal and Orsted Dal, an area seldom visited by the local hunters. They didn’t find conclusive evidence of the wolf being properly re- established: on one hand, they discovered that the northern valleys of Orsted Dal and Colorado Dal were home to far less muskoxen (the wolves’ favorite prey) than expected ; but on the other hand, a wolf’s den and scat from this year or last year were found on the way to Orsted Dal, and surprisingly another scat was found near Harefjord, several dozen kilometers on the other side of the Scoresby Sund.

Their next project focused on migratory birds, notably geese, as a propagation vector of the Avian Flu virus. Could the Arctic, where these birds come every year, be a reservoir of the virus? They took samples of water, ice, feathers and droppings. A third project intended to study characteristic traits of Arctic plants, and yet another fourth project focused on polar bears and their DNA relation to their Canadian cousins. Just 2 days before we arrived, a bear had been shot by locals near a hut for safety reasons, and we took samples of the skin.

A characteristic of the Lost Worlds expedition organized by Naturevolution is that scientific research is far from being the only purpose: images are as much important for us to raise awareness about the beauty of the “lost worlds” we explore and the necessity to protect them. This means that while the expedition is unfolding, we focus at the same time on recording a story and capturing it on video, which could sometimes doubles the time of any activity we undertake and create strain for the people involved.

We had a total of 8 DSLR, 4 drones, several GoPro and Osmo, with matching numbers of computers, hard disks, memory cards and batteries. With so many power needs for scientists and photographers, electricity was a daily concern. Not knowing whether we would get the Nomad solar panels and Yeti generators from Goal Zero in time, we had purchased a fuel-powered generator and 2 large car batteries. While the solar panels were undersized for the full scope of the mission, they proved much more reliable in the end. Due to poor quality fuel, our generator broke after 10 days and power bonanza was over for good. We then pulled as much energy we could from the Nomad 100 – and later the additional Nomad 20 we finally recovered from Air Greenland – changing the orientation of the solar panels every hour to catch as many Watts we could. It made us prioritize our electricity needs and understand what was most important from one day to the next.

The second phase of the expedition is now only starting. From mid-August to early September, it will take place in the beautiful landscape of Harefjord and the rocky coast at Sydkap. Stay tuned.